FRArt Why relooking at caricature today ?

- is created by Eleni Kamma

- is promoted by Académie des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Bruxelles

1. Interview

- has as interviewee Eleni Kamma

- has as interviewer Septembre Tiberghien

- type: Article

- ref: DOC.2021.121

- Creation date: December 21 2017

- Eleni Kamma, interview

- elenikamma-revuear2018_72.pdf

- application/octet-stream

- 556.07 KB

- download

The following interview was conducted in Brussels on December 21, 2017.

Art et recherche (A/R): What were the elements that set you on the path toward your current research?

Eleni Kamma (E.K.): The questions I encountered during the first year of my thesis led me to make this proposition. Since the beginning, there was a strong desire to work in three different territories, so that I would be able to compare them in a certain way. So I focused my attention on Belgium and the Netherlands, the two countries where I live and work, and on Greece, where I come from. My research question was framed as follows: How can local and traditional European forms of parrhesiastic theatre and urban scenography be a source of inspiration for critical artistic practices today? The research idea was to investigate different elements specific to Belgium, in relation to my thesis, whose subject matter is parrhesiastic theatre as a model for artistic practice. By parrhesiastic theatre, I mean a genre of theatricality whereby events or actions are staged by characters who courageously speak their minds through scenes of excess and laughter, that take place in common view and affect the spectators’ agency to speak their own minds. This includes most folkloric practices, such as the Carnival.

A/R: Why and how did caricature, as a research topic but also as an artistic practice in its own right, become apparent to you as a resource or a field of investigation?

E.K. At the time, I was just starting to read Champfleury’s Histoire de la caricature. However my decision to include caricature in my research project was more intuitive than rational. It is part of a certain kind of knowledge or know-how that is present in a culture. In Belgium, caricature was present in painting and literature, especially in satirical periodicals.

Belgian artists seemed to me very concerned with the act of naming. The negotiation between image and language is constantly present in modern art: in Magritte, Broodthaers, etc. And that’s really what fascinated me about caricature, this relationship between image and text.

A/R: What is interesting about caricature is that we don’t know whether text is subsumed by the image or vice-versa. In today’s society, we often get the impression that visual impact is more direct than discourse. But that wasn’t always the case. In the 18th century, for example, the traditional hierarchy of the arts put verbs ahead of all other forms of representation. This inversion of values occupies an important place in your investigation, it seems.

E.K.: By asking the question why relooking at caricature today, I sensed that this investigation could help me to better understand what it means to be a critical or engaged artist today. And how each person can find a way to take a stance during the era they’re in. My investigation of caricature led me to a genealogy of artists with more “literally organized brains”, to use Champfleury’s terms, who he distinguishes from those artists who are concerned solely with beauty. Champfleury also remarks that the painter of parody “attends to his time, is outraged by it and this outrage lends force to his pencil; but it is the facts that strike him, the news, current events”. These qualities could be attributed both to a caricaturist and a critical contemporary artist, in my view. And that is where my personal questions as an artist intersect with the concerns of my research. In the early years of my artistic practice, I was mainly working with drawing, and the output was received mainly on the basis of its aesthetic quality. And yet I also longed to introduce a more polemical dimension to my work. That’s where the desire came from to bring in language as a supplementary key for the spectator to read the work.

A/R: Outrage certainly is not rooted today in the same places it was when Champfleury was writing. What connection do you make between this historical reality and the current context for your research?

E.K. I found it very useful that it was such an old text, that I had to translate it and therefore really engage with it over a long period. That allowed me to resituate things in time. This return to older practices is at the heart of my artistic process. Not because I’m nostalgic, but precisely because it has the potential to revitalize latent powers that, if channeled into a specific context, can give expression to a political conscience. I try to avoid making any commentary on existing works, I find that limiting. But I appreciate it when the reverse process happens. For example, I drew this person who, for me, symbolizes anger, with a blank space instead of a mouth.

When it really comes down to it, who am I to talk about parrhesia? I’m neither an orator nor a performer, so how do I find a way to engage physically? How can I talk, to whom should I address myself? One way to resolve this question was to project myself into my drawings, to have an intimate relationship with paper as a surface in itself.

I found a caricature of Kupka dating back to 1902 in the popular journal “L’assiette au beurre”, which was entitled L’électeur aphone. I was amazed at how similar it was to my drawing. At the time, the author was denouncing the fact that a citizen with more money could have a bigger voice (votes). In the caricature, we see a voter with one voice, another with half a voice… and one without any voice of all: he’s been muzzled.

A/R: The relationship to the body and the question of which ethical posture one should adopt seem to be major components of your research project. I imagine that this influenced your decision to experiment with other tools for recording, like performance and video. Was this a conscious choice, a deliberate one, or did these media become necessary little by little as your process advanced?

E.K. I certainly don’t work linearly, I don’t try to answer questions in the order I ask them. It’s more about finding a way to bring the elements in question together, in a certain order.

A/R: How did you come to the idea of holding a casting for a parade in the future?

E.K. The parade is first of all a device or a model to help me explore the visualization, actualization and practice of aspects of parrhesiastic theatre. The model develops around sequences of mental images of a parrhesiastic theatre parade as an “event” to be filmed. This parade is founded on old, traditional forms, characters, events and manifestations of parrhesia. These are then transformed, with the help of drawings and objects, into a contemporary typology of characters, places, roles and their possible interactions. These interactions will happen through the appropriation, re-enactment, and rehearsal of certain acts. In the context of this research process, some of the characters are created with the idea in mind that they will be played by performers, who will wear costumes and accessories to interact with the public through a series of actions. The ‘casting call’ in the title functions at the same time as a reference to the process of preparing a film or theatre production and as an open invitation, an attempt to include the spectator.

From a conceptual point of view, the parade develops halfway between a cultural allegory for contemporary Europe and an invocation of a community surrounding ancient parrhesiastic rites. By exploring other ways of speaking—as suggested by the etymology of the word allos, which signifies “other” in Greek—and by producing arbitrary relationships between image and language, allegory has often been used as a weapon against instances of injustice.

A/R: Parades are closely related to political protests, in a way. Why pursue a form of representation with such a social connotation?

E.K. My reasons for using parades as a form for research are multiple. Whether for military, carnival or even protest purposes, parades form and address a social body. During Carnival, people shed their everyday individuality and gain an increased sense of social unity through the use of masks and costumes. The point of a parade is to show, to expose, to make visible—whether it be the power of a conqueror or the height of celebration. Parrhesiastic practices equally aim to make visible and exhibit, but they are concerned with issues such as an injustice done to a city or a corrupt leader.

A/R: You decided to implant your parade within an urban space, rather than on stage in a theatre. Won’t the results be harder to control, more random?

E.K. A parade engages with public space in two ways. It is a moveable temporary public space in itself and, at the same time, by theatricalizing the existing public space, it crosses it, permeates and perturbs it. A parade challenges the given order of things and therefore has the potential to activate and transform the spaces of the city it moves through.

My way of developing this parade is spread over four stages. These stages include the exercises, the cracks, the doubts and the spaces that exist between the will to share one’s opinions through comic situations with the public, and the actualization of such situations.

A/R: Where did you find the inspiration to create these characters? What are their essential qualities? How will they evolve?

E.K. My starting point is the development of several types of characters, both individuals and in groups. Although these people are fictitious, they are inspired by figures in popular culture, art, theatre and film that risk speaking their minds through scenes of laughter and excess. They embody traces of the comic traditions of their respective regions and move alongside the city’s urban tissue. Creating urban scenographies in motion, these characters demonstrate various strategies of language, image, and gesture as employed for parrhesiastic purposes. They do so by assuming positions of otherness.

A/R: Could you describe for us briefly which characters seem to you to be the most emblematic of this parade?

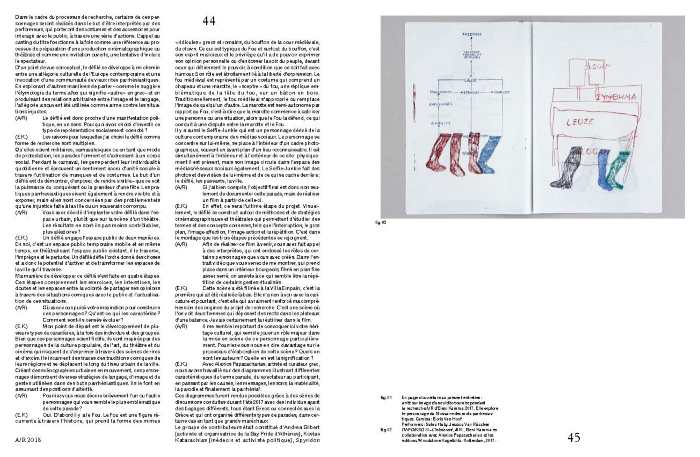

E.K. Sure. First there is the Jester. The jester is a recurring figure throughout history, who sometimes appears in Ancient Greece or Rome as the “ridiculous” mime, the buffoon or royal court jester of the medieval era, and the clown. The jester, and certainly the buffoon, is typically malicious in spirit and has the privilege of being allowed to express his personal opinion or be the voice of the people in the face of those in power, as long as its done with humor. His role is closely tied to freedom of expression. The medieval court jester is represented by a costume that includes a hat and a marotte, a scepter carried by the jester that portrays a replica of the jester’s face carved into the wood. Traditionally, the medieval jester appropriates or replaces the image of someone else. The marotte is somewhat autonomous from the jester, that is, the marotte can start satirizing a person or a situation while the jester takes a defensive position, which leads to an argument between the jester and his scepter. Then there is the Selfie Junkie, a character derived from contemporary social media culture. This character is preoccupied with him- or her-self, is always at the center of an image, and is often pictured against the backdrop of a recognizable place. The Selfie Junkie is both inside and outside that place: they are physically present in a real place, but their image circulates in the space of social media/networks. The Selfie Junkie takes photos and videos of him/her-self and of what lies behind them: the passers-by, the city, the parade.

A/R: If I understood correctly, the final goal is not only to document this parade, but to make a film based on it.

E.K. Yes, that would be the final stage in the project. Visually, the parade would be constructed using cinematographic and theatrical methods and strategies that allow one to study related terms and concepts, such as interruption, close-up, affection-image, action-image, and repetition. The three previous stages are brought together in the editing room.

A/R: Part of the process for making this future film involves a casting call for actors that can play some of the characters you have created. In the video excerpt that you just showed, shot in a rather upscale bourgeois setting and filmed using a very tight fixed shot, we witness what seems to be the rehearsal of certain ritualized gestures.

E.K. This sequence was filmed at Villa Empain, and it was the first one that we shot there. It has nothing to do with caricature and yet it really reinforces how I see the origins of this research project. In the scene we see two women placing words on the tray tables of a scale. I will certainly re-use the scene in the film.

A/R: It seems important here to talk about your cultural heritage, which plays a major factor in how you dramatized this particular character. Could you tell us more about how you developed this scene? Who are the authors? What is its meaning?

E.K. Together with Greek artist and curator Alexios Papazacharias, we worked on diagrams demonstrating different aspects of the term parade, ranging from viewers and participants, their motivations, messages and sounds, to materiality, parody and finally, parrhesia. These diagrams were based on a series of discussions conducted in the summer of 2017 with individuals who all had different kinds of baggage, all of them Greek or connected to Greece, that were organizers of various kinds of parades. In some cases they were even grand marshals of a parade.

The group of contributors consisted of Andrea Gilbert (activist and organizer of Gay Pride Athens), Kostas Katarachias (doctor and political activist), Spyridon Papazacharias (officer in the Hellenic Air Infantry), and Thanasis Deligiannis (composer). Maria Konti (artist and therapist) generously provided us with information about techniques that can facilitate communication and creativity in a group setting.

I used these diagrams and discussions when drawing the different characters in the parade.

In the video in question, the scene was from the Glossary of Parrhesiastic Words. As a theatrical figure, the Glossary moves along the urban tissue of the city, demonstrating the heaviness of words she carries with her, words made of brass, hanging from metal chains around her body. She carries a balance to weigh and compare the heaviness of words against each other. The words are hammered, in reference to value systems and old Greek vows. Although I am a visual artist, I often have recourse to language, sound and the input of language to create a poetic image. Maybe that’s my way of protecting myself from being seduced or deceived by the visual, to avoid being trapped by beauty.

A/R: What made you decide to use Villa Empain as the setting for shooting this particular scene?

E.K.: To start with, the Villa is a beautiful example of Art Deco architecture. It also has a rich history due to the number of owners that lived there. The building is, in my opinion, a monument of contestation, in terms of the struggle between public and private rights to beauty and cultural heritage. It was successively a private residence, a museum for decorative arts offered by the Baron Empain to the Belgian state and then Gestapo headquarters during WWII, then the embassy of the USSR, then an exhibition space, headquarters for RTL, etc…. It has been subjected to pillage, long periods of vacancy and abandonment. Since 2010 it operates as a cultural center, hosting exhibitions, concerts and conferences.

A/R: Are there any other emblematic places in Brussels that you noticed and that have nourished your analysis of local folk traditions?

E.K.: At the very beginning of the project, I asked the dancer Sahra Huby to contribute to the research. In May 2017, Sahra, Elena Betros (Brussels-based artist) and myself were immersed for two days in intense discussions regarding my readings and my notes. For three days, Sahra assumed the role of a contemporary jester, caricaturing people who take self-portraits using selfie-sticks. She also developed the Selfie Junkie character that we talked about earlier. She moved among people, exaggeratedly imitating them and making fun of herself at Grand-Place in Brussels. She became a selfie junkie amongst all the others, provoking many reactions from tourists. Sahra, Pim Herkens (Brussels-based filmmaker), Elena and myself documented this research process, Sahra’s actions and the reactions of people watching her.

A/R: Looking back on your original intentions, how would you define or talk about the concerns of your research now that you have begun your process, from a formal artistic standpoint as well as from a conceptual and/or theoretical one?

E.K. First of all, examining caricature from a political point of view was supposed to be the central topic for the research, but then I realized that my expertise was rather limited, as I hadn’t lived long enough in Belgium and was not proficient enough in French or Dutch. As a result, I turned to Internet culture, which is more universal, to explore the modes of communication and ways in which these tools forge our identity. Then, I decided to re-situate these issues in the context of a parade. When I started, my research was quite vast, with three main axes. Then, certain aspects gained precision and others were left to the side.

A/R: The question of new media and the impact of caricature on the Internet, which tends to reveal politicians as caricatures of themselves, was already part of your initial research axes. What explains your choice to distance yourself from these issues?

E.K. As I explained before, I started with a desire to investigate caricature by reading and retracing its history. I visited libraries, museums: the Belgian Comics Museum, Museum BELvue, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Marc Sleen Museum in Brussels, James Ensor at Ensorhuis and at Mu.ZEE in Oostende. I read a lot. My starting point was Histoire de la Caricature by Champfleury (ancient, medieval and modern) at the end of the 19th century. The three volumes that I used contextualize caricature in Europe at different historical times. Then I continued with other resources. By looking at ancient examples of caricature, I grew more and more interested in the role of the media. I collected images and texts illustrating how caricature relates to political attitudes at various historical moments. I examined the role of the media in the production and distribution of caricature. My goal was to think about the place of caricature today by looking through the lens of the past. My research led me to better grasp how caricature relates to the popular media of each period. In Belgium, established as a nation in 1830, the power of political caricature is visible primarily in drawings and sketches that illustrate historical events. The development of printing techniques (lithographs) allowed for images to spread throughout an even greater public. Printed matter (periodicals and journals) was the popular medium of the time, which is perfectly in line with the role of the citizen subject in the 19th century. Today, the most popular media is indisputably the Internet.

The subject of my research was progressively re-oriented toward how we have become caricatures of ourselves across different social networks, in our behavior and our poses. My process for developing these archetypical figures is increasingly inspired by behaviors qualified as addictive, which mirror our own reflexes and bring about a kind of self-awareness.

Festivities like the Carnival, celebrations and parades are the sites traditionally identified for the production of communal laughter. When individuals participate in these kinds of events, they are essentially looking at the world from a personal and affective point of view, embodying the political in society through their participation. We are currently witnessing another kind of participation through social media/networks and using instruments like selfies and selfie-sticks. In a selfie, an individual becomes a character layered over a context that cuts him or her off from her agency. Rather than put the accent on the subjectivity of each person in the process of individuation, the selfie-stick allows the individual to be flattened into an image.

A/R: Did you draw on any theoretical resources and if so, which ones? What do you think they contributed to your research?

E.K. These back-and-forths between literature and “doing” are essential to advancing my work. I start with books, reading and language, in order to arrive to an image. In addition to Champfleury and the authors I already mentioned, who are directly related to the social and visual aspects of caricature, my research was also influenced by thinkers like Chantal Mouffe, Mikhail Bakhtin and Anca Parvulescu. I find her use of language, and more specifically her notion of the archive, her descriptions and her anecdotes to remind the reader of the materiality of laughter, particularly fascinating. I’m in the middle of reading Bifo right now, Phenomenology of the end. Cognition and sensibility in the transition from conjunctive to connective mode of social communication. It’s interesting to see how my interests and thinking have been redirected thanks to this period of research on caricature.

A/R: The authors you mention seem to agree on the fact that technological progress and the use of new digital and information technology tools have deeply and permanently altered our modes of socializing and learning. Do you think this could pose a threat to our freedom of expression and operate as a kind of filter or self-censorship?

E.K. Obviously the way we communicate today affects how we feel and think. About a year ago, I did an interview with a blind woman. She works in human resources and regularly interviews people for the recruitment process. This woman is capable of discerning a good candidate from a bad one simply by listening to the sound and spatial orientation of their voice. She knew if the person was reacting to her disability or if they were showing a loss of interest, for instance by turning their head.

It seems that we could draw analogies between a blind person’s spatial awareness and our use of virtual spaces. As a user, the entire world seems within reach, but only abstractly, through the computer, while meanwhile it is materially disconnected from my own body. And so our senses are fundamentally in conflict or at least separated from their center of emission and reception. In a larger sense, to communicate today, it isn’t necessary to physically embody a position, a representation is enough, and this has an impact on how we speak up, how we critique or joke around, and how we perceive the potential scope of the social body.

For example, the Arab revolutions were made possible via social networks. But once the people were united, in person, they didn’t know what to do, how to organize themselves. Virtual relations are very different than those we can have in the field, in our daily lives. I can’t exactly justify it now, but I think that this is a trajectory I’d like to follow and investigate. In an interview, the Greek poet and leftist activist Yannis Ritsos (1909-1990) talks about parrhesia by saying that our senses nourish the brain and not the reverse. I think he’s right.

A/R: To conclude, could you talk about the results of your research, or do you find this term inadequate? If there is a result, how is that different than a finished piece? And if the word “result” is inadequate, how would you call this work?

E.K.: I prefer to use the term “residue” or “trace” rather than results. For me, the results are fragments of presence that come by drawing or through images, objects, gestures. It is a part of the process. When we consider artistic research, I think we have to give more weight to the process than to the result. Throughout all these years, I fought to have my drawings seen as precise “instants” or highlights from a continuous creation and not as definitive results, which I judge to be a complete misinterpretation. Now I have the impression of arriving at the same thing via research. That said, even though I’m really interested in process, of course there are concrete stages, moments when one can observe the progression.

A/R: Would you allow yourself now to talk about this process?

E.K. Yes, I have more confidence. How you communicate about your research, how you talk about the process is also part of the results or the “residue” as I call it.

A/R: If it doesn’t come to a result, what punctuates or accentuates the work? Is it a movement with no end?

E.K. I tend to collect a lot of information in the form of images and texts and little by little, I start to test them. Then there’s a moment when I make a selection and only hold on to what is important in that excerpted material. That’s the sign announcing the end.

At the moment, I’m still collecting, and this process has not reached its end. But what is clear to me now, is the frame. It’s obvious to me that I should continue in this direction and that I will be busy with the film for the next two years. I think that at a certain moment, I will have exhausted all the questions, and that will be the end.

A/R: What can you say about this result or absence of result? How would you assess this experience?

E.K.: For me there have been and will still be several steps. First, there are the characters, second, the way they interact. And the way in which we film them. They are complementary. I like the idea that these characters echo one another. I think that produces something. The materiality of it is important, things must take on a physical dimension in order to be understood.

Caricature is exaggeration and can help to reveal certain things. By looking back on the power of caricature across the ages, and by seeking to understand the reactions they produced in people, sometimes very irritated reactions, we can use that as a method for revealing the intimate thoughts inhabiting them. The prejudices, clichés, etc… in this way, we also touch on public space.

My experience of this research period on caricature can be summarized as follows: thanks to the grant received from A/R, I gained new insights from my theoretical readings and I experimented with and materialized aspects of my research through drawings and objects. I also initiated an inventory of caricatural movements and expressions, which took the form of mini-test performances in public space, in collaboration with the dancers Sahra Huby and Jessica Van Ruschen. These tests were documented by Boris Van Hoof. I think the project would have benefited enormously from further explorations of the relationship between individual bodies and a collective body in urban space, where a political meaning can be produced through their interaction. It’s a shame that it wasn’t possible to guide a workshop with the students of Espace Urbain-ISAC (dance) due to the fact that the curriculum was already set before I arrived. But I still have some “traces” or residue to share and communicate through the video documentation and my presentations. And the inventory will now be available for the next participants and can be elaborated further. I think there is something to learn from all this to improve things for the next time. I should add here that my concern is not to determine how I can get people to participate, but to find a way to define a frame that might awaken their desire to enter and fill it. At the end of this period, I realize more and more how important it is to rehearse, to repeat and that my research is a permanent rehearsal toward creating an agonistic space. Parrhesiastic exercises are not about succeeding or failing, but they offer a world outlook, an attitude for daily life that must be practiced and repeated every day. And the limitations, blockages or failures are part of the game.

A/R: Caricature has the power to provoke, which it uses to prod the social abscess, but it can also be used as preventative medicine.

E.K. I totally agree. I think that’s why I would like this film to be seen and for it to touch a wide audience. Maybe it could be shown on the Internet and in that way, return to the source.

A/R: Was this work collective? Is this dimension already a mode of transmission for the research or does it fulfill another function? Did you have any encounters with the public? Are presentations another mode of transmission? Were there any meetings with students? Do you consider them a kind of “network” for your research, a way of transmitting knowledge, of engaging students with the work?

E.K.: There are really many negotiations between the individual and the collective in what I do. I consider my practice to be situated between a monologue and a dialogue. More precisely, my attempt is to develop a nourishing schema that takes the form of a Mobius strip. This schema constantly moves between me, in the role of an individual artist who practices drawing—which could be interpreted as a monologue—and the group. The group embodies the dialogue between individuals and myself, and draws on activities like walking, speech, performative events, collaborative journals, in order to communicate their findings.

It is an individual project that evolved through the participation of others. I think that the impulse comes from me, since I am the author of the project, but my desire is for people to also find their place within it. The dancers were very critical and brought up many questions. In a way, I started with a very open form and invited collaborators/participants to help articulate the project. It is important to work on the mise-en-scene, without controlling everything. That makes part of a much larger discussion, I think, that concerns how we create knowledge. Is it as individualistic as we claim it is? I don’t think so. For me, the myth of the artist working alone in the studio is dead.

2. Why relooking... interview (jpg)

- has as interviewee Eleni Kamma

- has as interviewer Septembre Tiberghien

- type: Interview

- ref: DOC.2021.241

- Creation date: December 21 2017

- duration: 0:00:00

- Interview 1

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_1.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 42.2 KB

- download

- Interview 2

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_2.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 1.35 MB

- download

- Interview 3

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_3.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 236.68 KB

- download

- Interview 4

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_4.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 259.99 KB

- download

- Interview 5

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_5.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 231.15 KB

- download

- Interview 6

- EleniKamma-revueAR2018_72_Page_6.jpg

- image/jpeg

- 459.7 KB

- download